Allison Schrager: Raiding your 401(k) to buy a house should be an option

Published in Op Eds

I have a confession, shameful as it may be for someone who has spent decades studying retirement policy and advising individuals and institutions on how to save for and think about retirement: When I bought my apartment a few years ago, I raided my retirement account for the down payment.

Yes, I am well aware of the sacrosanct rule — never take money out of a retirement account before you turn 59.5 — but I did it anyway.

And you know what? It was among the best financial decisions I’ve ever made. I am not sure it’s right for everyone, but it should be an option, and President Donald Trump is right to want to make it available to all Americans.

My circumstances were exceptional. I bought my apartment during the pandemic, when people were allowed to take up to $100,000 out of their accounts without paying a penalty. If I’d had to pay the penalty, it would have been a bad decision (as it was, I incurred a large tax liability, which took three years to pay off).

The president’s plan would allow prospective homebuyers to take money out of their 401(k) accounts without penalty to make a down payment. It is worth noting you can currently take up to $10,000 without penalty if you are a first-time homebuyer. The details of the proposal are still being worked out, but presumably the limit would be higher and the option available to all homebuyers.

Does that mean everyone should spend their retirement money on a house? Not necessarily. For me, there were two main reasons I took advantage of the program, and neither had anything to do with the pandemic. One was the record low mortgage rates at the time. The other was my personal financial situation.

When I looked at my finances to figure out what I could afford, I was stunned that almost all my assets — more than 80% — were in retirement accounts, and most of those were in stocks. Maybe that’s because I tend to overprioritize saving for retirement, or because I’ve worked at places that offered a generous match, or because I wanted to use most of my disposable income to feed my shopping habit. But even I had to admit the amount of my portfolio in retirement accounts violated the life-cycle investing principles that I was trained in.

The goal is smooth, predictable consumption — including housing today, not just retirement income for tomorrow. It also occurred to me that I could stand to diversify a bit and have less in stocks and more in real estate (at least that’s how I explained my decision to the co-op board). If I took on homeownership, I also needed to be more liquid, which made reducing my retirement accounts the right choice.

From a strict financial standpoint, my decision is hard to defend: Stock prices have gone up more than real-estate prices in Manhattan since 2021. But rents have increased even more, and I’ve locked in my housing costs at a low mortgage rate and am building some equity. For me, and assuming apartment prices don’t completely crash, it was a good decision.

Again, and as grateful as I am to have had that choice, it does not make sense for everyone. In general, cleaning out your retirement account to make a leveraged bet on a single asset is not a wise financial move. It’s better to build up diversified savings before investing in real estate, and it’s important to have a healthy retirement balance.

About 55% of American households — a record high — have retirement accounts of some kind. On average, those accounts make up 27% of their net worth, a figure that falls to 22% for people under 45. Even though this group is relatively rich in retirement assets, they are often the ones struggling to afford a down payment.

Another concern is that too many people will have less money for retirement. A house is not just a place to live today; financially speaking, it tends to be people’s largest asset in retirement. Most retirees are overexposed to housing. Among retirement savers over age 65, home equity makes up 50% of their net worth; cash assets are only 28%. Absent better reverse mortgage options, this keeps retirees from spending a large share of their wealth, and means some are scrimping on their non-housing expenses.

There is also the possibility that this plan, by making more cash available, will increase demand for housing — and if new housing isn’t built, that will only push prices up further.

Policy issues aside, if this proposal becomes reality, the main issue facing most Americans will be whether they should use their retirement money to buy a house. I don’t mean to brag, but given my academic expertise and homebuying experience, I may be uniquely qualified to address this question. And my answer is this: It depends.

For me it was a good decision, because I needed diversification and could take advantage of unusually low mortgage rates. If buying a home leaves you overexposed to housing, under-saved for retirement, or taking on a mortgage you can’t afford, then it’s probably not a good option. But it would be nice to have a choice to make.

_____

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

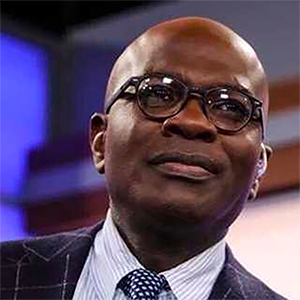

Allison Schrager is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering economics. A senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, she is author of “An Economist Walks Into a Brothel: And Other Unexpected Places to Understand Risk.”

_____

©2026 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com/opinion. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments